The Stays or Corsets of the Regency era

The Empire Silhouette

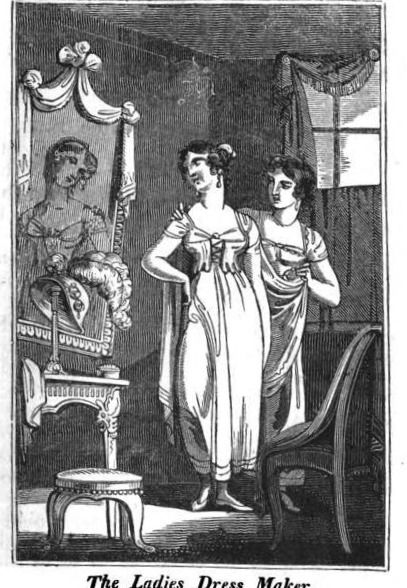

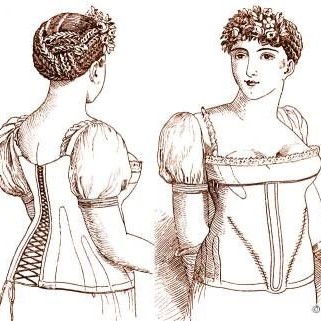

This new style of dress, with the iconic high waist, was based on the examples of Greek and Roman dress, and was supposed to be more natural. And the shape of these dressed certainly looks more natural than the style in the time of Louis XVI. However, take a close look at the ladies in the engraving above. The idealized form in this period is a long column-like posture, and the fullness of the breast is situated nearly at the level of the armpits. The undergarments would have to provide quite a bit of lift to acquire this shape. And we thought that push up bra’s were something quite modern…

We have quite a few examples of both stays from the Rococo era and corsets from the Victorian era, as shown above. The first giving the body a inverted triangle shape, and the second defining and tightening the waist to achieve that hourglass figure. These shapes are very easily recognizable, and if you search for “Rococo stays” or “Victorian corset”, you’ll no doubt find lots of pictures practically identical to the ones above. But we don’t have a iconic style of corset like this from the regency era. So how did we get from A to B?

From Stays to Corsets

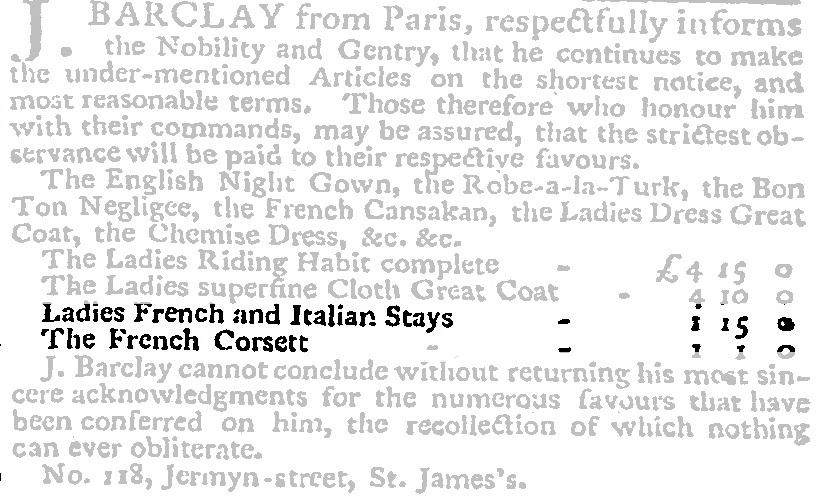

As you must have noticed, I use both the words “stays” and “corset” in the paragraph above. Not only the design of the corsets changed during this period, but also the name by which we refer to the garment is different. The structuring garments from the 18th century and earlier are called stays. But at the end of the 18th century, the term corset appears.

In this ad from 1789, we see the words corset and stays used simultaneously, referring to two different types of garment. While the word stays was used to describe the stiff fully boned garment shown above, which created that inverted triangle shape, the term corset, or corsette, referred to a supportive garment that was lightly boned or quilted. The word corset comes from the old french “cors”, meaning body. So this garment was literally supposed to be shaped more like the natural body.

Multiple corsets lead to an Empire waist

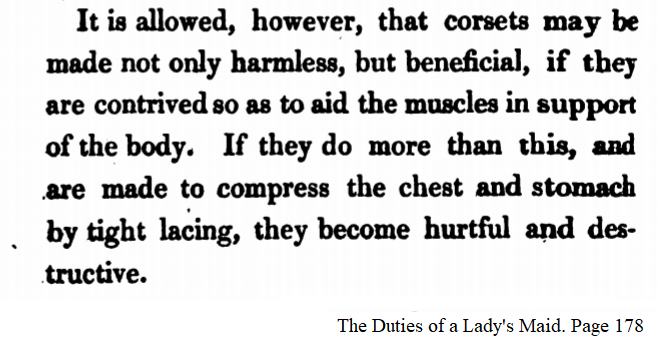

So what is a lady to wear around 1805? When we look at examples of stay’s in museums, like the page above from the collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute, we see a few different shapes all existing next to each other. The corset on the left is dated 1820, but the other three are all dated “early 19th century”. However, If we look the corset on the bottom and the corset on the right, a few differences are evident. The corset on the bottom gives more definition at the waist and has a medium high bust line, while the corset on the right gives a less defined waist with a more column like silhouette and has a very high bust line. I would therefore argue that the corset on the right was probably worn earlier, I would guess around 1805 to 1810, while the bottom corset is probably from around 1820, like the one on the left.

These two stays are from the end of the 18th century, around 1790 to 1800. As you can see, these stays form a sort of middle ground between stays and corsets. These days they are sometimes called transitional stays, because they mark the transition between stays and corsets, but back in those days, they were just called stays. The first one is still quite heavily boned, but the displaying instead of flattening of the bosom is already happening with the cups of these corsets. Gowns from this revolutionary period still had some fullness in the front, so the stays didn’t need to go all the way to the hips to provide a nice line for the dress.

These full length corsets seem to have been most common during the regency era for formal dress, for ladies that needed more support, and just for everyday. These corsets were laced at the back and had a wooden busk in the front. This busk was separate from the corset, sometimes lovely carved, and slid into a pocket in the middle of the corset. This busk provided separation to the breasts and ensured an upright posture. Some corsets had a few light bones in them, mostly on the seams, to provide some structure, but nowhere near as much as the stays from the period before. But a lot of stays just used quilting (sewing different layers of fabric and padding together) or cording (sewing lengths of cord between the pieces of fabric) to provide the necessary structure. All corsets from this period had straps. In the front these were spaced quite far apart, attached to the outer sides of the corsets, while on the back they were quite close together, more towards the middle of the back. This placement also aided with the upright posture, and kept the straps from slipping off the shoulders. The cups of the corset were created by inserting a triangular pieces of fabric, called gussets. Together with the structure provided under the breasts and the straps pulling everything up, these ensured a high breast position. The top of the corset usually reached only to the middle of the breast. The chemise under it ensured that the fullness of the breast would not spill over the top.

Which corset to wear?

So, back to the question at hand; what sort of supportive garment should you wear under an empire line gown? I think it all depends on the time period you want to portray, whether you want a more formal or informal look, and your figure. All the examples above will provide you with a light supportive garment and give you a raised bust line, all period accurate. If you want a more informal look and easy dressing, you could go for the Half Stays a la Paresseuse. A front lacing pair of short stays would not be my first choice unless you do indeed fall into those groups of pregnant, breastfeeding, or you have a disability. But as you can see from the example from the Victoria and Albert Museum, front lacing garments did exist, and are still period accurate.

I think the most important factor in considering what kind of corset you want to wear is your figure. This is not about your size, but about the proportions of your body relative to each other. Take a look at the garment style you want to create. A fashion plate would be perfect for this, because those display an idealized version of the perfect body shape of the time. And now look at the proportions. Where is the bust line relative to the shoulders? How long is the body compared to the legs, or the other way around? Is the waist quite defined in comparison to the hips and bust, or is it longer and straighter? Now look at your body. How are your proportions? And where should your corset provide lift or structure to resemble the proportions fashionable at the time?

I will take my own figure as an example. I have a quite defined waist, a shorter torso, a bigger bust, and a bit of fullness around the stomach area. The gown I want to wear is based on an example from around 1802. The bust line is quite high and the torso has that long column-like shape i mentioned earlier in this post. This means that to make this gown look period accurate on my figure, I need my corset to provide quite a significant lift to the bosom, and even out the fullness of my torso, making my waist look less defined and my torso look longer in comparison.

Of course a corset, especially a lightly boned one common in this area, will not drastically change your figure, but it can help you to subtly adapt the way your body is perceived by giving you structure in the right places, so your garment looks more historically accurate. For me, considering the fact that I do not have the ideal column-like shape for an 1802 lady, I will go with a full corset, with a front busk and back lacing. I found this beautiful example, from the Boston Museum of fine arts. This one has that typical column-like shape with no defined waistline, which draws the eyes up to the empire line underneath the bosom.